Red Hot

Mad, Bad, and Dangerous to Know

Cream, formed in London in 1966; disbanded in 1968. Rock music’s first super group, and the first band I dared to call my favorite.

At the time of discovery, I only knew of Eric Clapton, who led me to the group. My mother, with her penchant for tragedy, like her husband, first put me onto him when I was young when she told me how his son died falling from the 49th floor of a Manhattan apartment building. From there, I discovered on my own that Clapton was a guitar god. I learned about Jack Bruce and Ginger Baker when I arrived at Cream. Before then I only knew Cream’s music superficially— from Goodfellas, that famous “Sunshine of Your Love” scene. It wasn’t until maybe late high school or freshman year of college that I really got to know them and get into them heavy.

A friend of mine and I, wanting to avoid paying for two separate premium accounts in the days before family plans, decided to share a Spotify account. I think it was mine, and he just sent me the money every other month. It didn’t work of course. We would inevitably want to listen to music at the same time, hundreds of miles away at school in our respective states, and boot each other off. This was the fall, before campus would freeze over and I’d know what a real winter was, an Upstate New York one, with wind gales like a thousand pins on your face. I would walk down the streets, no one there, listening to Disraeli Gears until James Taylor or Eagles would cut in.

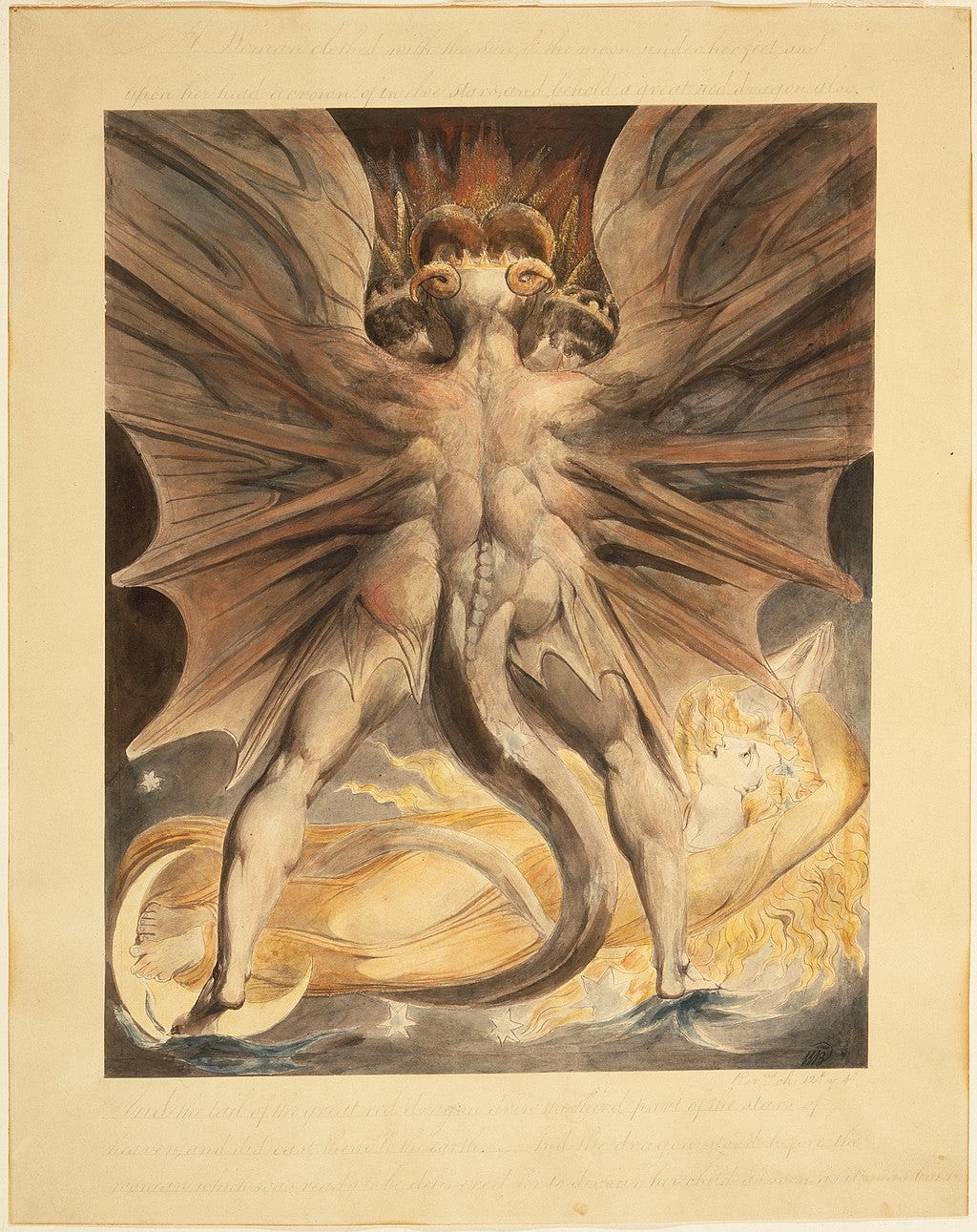

I liked the crashing and swelling of Baker’s drums; how Clapton’s guitar danced like the needle on a speedometer. I liked Bruce’s voice, which was like an omniscient narrator. It was inexplicably cool, in an aesthetic way, how they just played music and didn’t write lyrics. They outsourced that to a poet named Pete Brown, who had a kind of William Blake flare to him, evocative of his paintings rather than his poems. Specifically The Red Dragon and the Woman Dressed in the Sun, the one Francis Dolarhyde eats in Red Dragon and that gives the book its name. Anyway, I thought they were cool.

My music taste has since grown but ultimately hasn’t changed. What I like has sort of propagated and manifested itself in other forms. Taste is aesthetically driven, the choice is always deliberate even if it appears as something uncharacteristic initially. The connections always reveal themselves, sooner or later. Part of the enjoyment is unearthing them for yourself.

I love when a song you’ve listened to a thousand times sounds different on the 1,001st and you’re able to explore something you thought you know in a completely different way. Lately that has happened with Led Zeppelin’s “Fool in the Rain,” which, if you listen to classic rock radio anywhere in the NY Metro, you’ll hear way too much. If I had a sailboat, that’s what I’d name it. Maturing is realizing that the piano part in the middle in incredible— a contained burst of energy that is best experienced when driving fast with the windows down or while running.

(It’s also the reason the band never played it live. The complicated arrangement would have required more musicians to pull off in concert and it was just too much of a hassle.)

Eric Clapton is still God; that hasn’t changed. At least for me it hasn’t. But I’ve changed in the sense that I’ve come love the drums and see them as the best part of rock music. Maybe because it best captures— and is the best outlet for— rage. That’s why Ginger Baker played them so well and is arguably the best at it. Now I wouldn’t hate you if you suggested Neal Peart, but he’s still in a different league than Baker, who at his core was not a rock drummer but a jazz drummer, in influence and practice. Cream itself was a jazz-oriented project, a fusion of many genres— Bruce himself said so. They improvised and set the mold and morphed into rock or psychedelic rock, a label given to them but never embraced by them. Baker’s riffs are stuff out of Miles Davis and Art Blakey, from the days of big band music and arrangements, they are so much more improvised and free, not under any constrictions of genre or attitude.

Baker was a curmudgeon to say the least, definitely a disagreeable guy, but there’s nothing off-putting about his sound; it’s like he was possessed, no, it’s as if he was devoid of any soul, any personal incumbering quality and was just a vessel. What made Cream great (a lot of it had to do with Jack Bruce, but you can read up on him on your own) is that they worked around Baker’s style of playing, which is crazy to think about, because it was so wild and all over the place and yet perfectly in time. A Clapton solo like in Crossroads that flows and colors a song is really secondary when you listen to the structure the drums build.

I have come to identify with Baker’s rage, for better or worse. His was a kind of fearless restlessness, burning passion, burning like his hair. He is Ginger because of his hair— his real name is Peter Edward. He burned through lives the way the rest of us change underwear.

The other day I found a clip from the Beware Mr. Baker documentary. Chad Smith, drummer for the Red Hot Chili Peppers and Will Ferrell doppelganger (or perhaps the other way around) tries to light Baker’s cigarette during an interview and is angrily swatted away. Smith can only laugh it off and say “Shit!”, lighting his own cigarette and giving the moderator of the interview a look. The documentary opens up with Baker assaulting the director, who managed to convince Baker to let him live with him at his South African compound and write a story about him for Rolling Stone about.

Baker once drove from England to Nigeria, across the Sahara in a dilapidated Range Rover. That in itself is another documentary. He moved to Tuscany to start an olive farm. While in Nigeria he opened up a recording studio where Paul McCartney wings composed “Picasso’s Last Words (Drink to Me)” for Band on the Run in 1973. He raised polo horses in Colorado and made B movies in Hollywood (B movies is generous). He moved to a beautiful farmstead in Tulbagh, South Africa, to escape legal trouble in the US. You see the open space and his Rhodesian Ridgebacks running alongside him in Beware Mr. Baker. He was married four times and had three children. His tendency to slash and burn calls to mind Neil McCauley’s credo from Heat: Never get attached to anything that you can’t away from in 30 seconds flat if you feel the heat coming around the corner. He was so himself that he practically burned a spot for himself in time.

It comes from the fiery soul. I’ve known a few gingers growing up. One of them I was in school and spoke with regularly. She was a sharp-tongued, incredibly literate girl who would balk at the way I just described her. We had a prickly back and forth, all in good fun though. She had a very distinct fashion sense. She wore dresses like the ones the secretaries in Mad Men wore. She herself was of another era, probably the Sixties (her favorite book was To Kill a Mockingbird, a book I’ve recorded many false starts with, don’t know if I’ll ever pick it up again. She’d probably balk at me saying this too, and for using the word “balk”. They were dresses, ones with ruffles and pleats that matched her headbands. She was not afraid of anyone, so it seemed. She would hit a man. She was real, like the way the world looks after waking up from a nap out in the sun; real like roadkill, the way something that was once animated by life is no longer, but because it’s not, is much more tangible.

Two instances come to mind: there was a kid who died in our school. He was our age, in the fourth grade. Ten years old and fought cancer for half his time on Earth. The principal went from class to class to break the news. She was a rich yenta or in the process of becoming one, whose jewelry jangled and her hair didn’t move. She was upset but her makeup didn’t run— a professional, I’ll giver her that. I cried. I’ve always been a pussy, but this was sad. They took all the visibly distraught kids to the office, a quarantine of despair. She, Red, was there. I remember her taking my hand, squeezing it and not letting go. Eventually she did, obviously, but I don’t remember when.

Another time— this was much later, in high school— I was at a house party. I should say we were at a house party because she was there too, but we didn’t come together. It was time to go. Those snaky private roads seemed to wind more at the end of the night, darker somehow although there was visibly no less light than two or three hours ago when the night began in earnest, socially I mean. We were in the same car, dropping her off first. In her neck of the woods (literally) the houses have long, sloping driveways obscured by brush and hidden from the road. Real money provides privacy. Seclusion is a symptom of the Upper Middle Class on Long Island. You’re not backing out or turning around on one of those driveways, so we walked up, her and I, and approaching her door she asked if (more like commanded) I was going to kiss her. It was chaste, tasteful, maybe even a bit prude; an extended peck, that either before or after she revealed to be her first. Given my lack of game it’s surprising that it wasn’t mine too. Her lips were tight and closed against mine. She pulled away. All I remember for sure was standing there after in the dark.

I think back to a trip on the Jersey Shore with another ginger, a friend of my friend’s brother, who wore DC shoes and lacrosse shorts constantly, swore like a sailor and could climb anything. On the beach one night I joked and said he had “ginger-vitus".” He was two years older than me (I was 12) and threw me in a headlock and onto the floor. We rolled around, his freckles lost in the sand.

Wrath hath no fury like that of a ginger. Take a criminally neglected and underrated example: Dolores Claiborne.

(Not the novel but it’s film adaptation, which, at least to me, are two different things entirely. It’s all about perspective and how it serves the story. Perhaps for it’s form, the first person POV of the novel serves best to give the narrative some color and fill in those psychological gaps at a depth at which a film just can’t reach. However, I don’t think the story needs it to go there. The film uses omniscient third-person, widening the scope of the story, as well as doing away with unnecessary characters. It is the rare case of the film not only being better than the book, but improving upon it as well.)

Vera Donovan, an icon, bitterness and schadenfreude incarnate, played to perfection by Judy Parfitt (if you don’t know her, watch this film and you will. In fact, you’ll never forget her). Vera is the owner of the house on a hill on the jagged Down East coast (every gothic tale has the house) which the titular protagonist maintains as head housekeeper. Dominating and cruel and as intimidating as her house. “She’s a bitch, she’s abusive, she’s cheap,” is how one character describes her in the film.

“Sometimes you have to be a high riding bitch to survive,” Donovan says in what is her most prominent scene. “Sometimes being a bitch is all a woman has to hold onto.”

Readers of Stephen King can recognize those instances when he jumps the shark, but even then he creates characters that leap off the page fully-fleshed out; characters that are a dream for actors disciplined in their craft. In the Venn diagram of talent, writers and actors overlap in one spot: empathy. Parfitt’s gift allows that inner rage, that fiery, tempestuous spirit to burn through— her MCR1 gene fully realizing itself here.

“Sometimes you have to be a high riding bitch to survive,” Donovan says in her most prominent scene. “Sometimes being a bitch is all a woman has to hold onto.”